RESEARCH

Hawthorne -

For most of my career, I kept quiet. I conducted my research, wrote the reports, and followed protocol. But I knew. Quietly, so did others. Over the years, a pattern emerged—anomalies in plant behavior that didn’t fit the accepted models of biology. Memory, communication, responsiveness to human intention. These were not isolated findings or fringe theories; they were documented in peer-reviewed studies, published in respected journals, and then quietly forgotten. Buried not by accident, but by design.

Government agencies and institutional gatekeepers have long maintained a rigid definition of consciousness—one that excludes anything without a brain or central nervous system. It’s a convenient framework. It keeps the ecological hierarchy intact. But research from Monica Gagliano, Cleve Backster, and Suzanne Simard—among others—has made that framework increasingly difficult to defend. The data is there. The implications are unavoidable. What follows is a brief, direct presentation of that evidence. I am not here to speculate. I am here to document what has already been shown, and to make clear what those in power have chosen to ignore. Plants are not passive.

They are not insentient. And the truth has been in front of us all along.

1. Plants Have Memory (Mimosa Pudica Study - Monica Gagliano, 2014)

Monica Gagliano's groundbreaking experiments with Mimosa pudica, commonly known as the "sensitive plant," revealed that plants could exhibit a form of learning and memory. By repeatedly dropping the plants in a controlled, non-harmful manner, she observed that they eventually stopped closing their leaves, indicating they had "learned" the stimulus was harmless. Remarkably, this learned behavior persisted weeks later, suggesting a retention of memory without a central nervous system.

This study challenges traditional notions of intelligence and memory, which have long been associated exclusively with organisms possessing brains. Gagliano's work implies that plants have evolved complex mechanisms to interact with their environment, allowing them to adapt based on experience. Such findings prompt a reevaluation of plant behavior and cognition, urging the scientific community to consider the possibility of a form of intelligence in flora that operates differently from animal models.

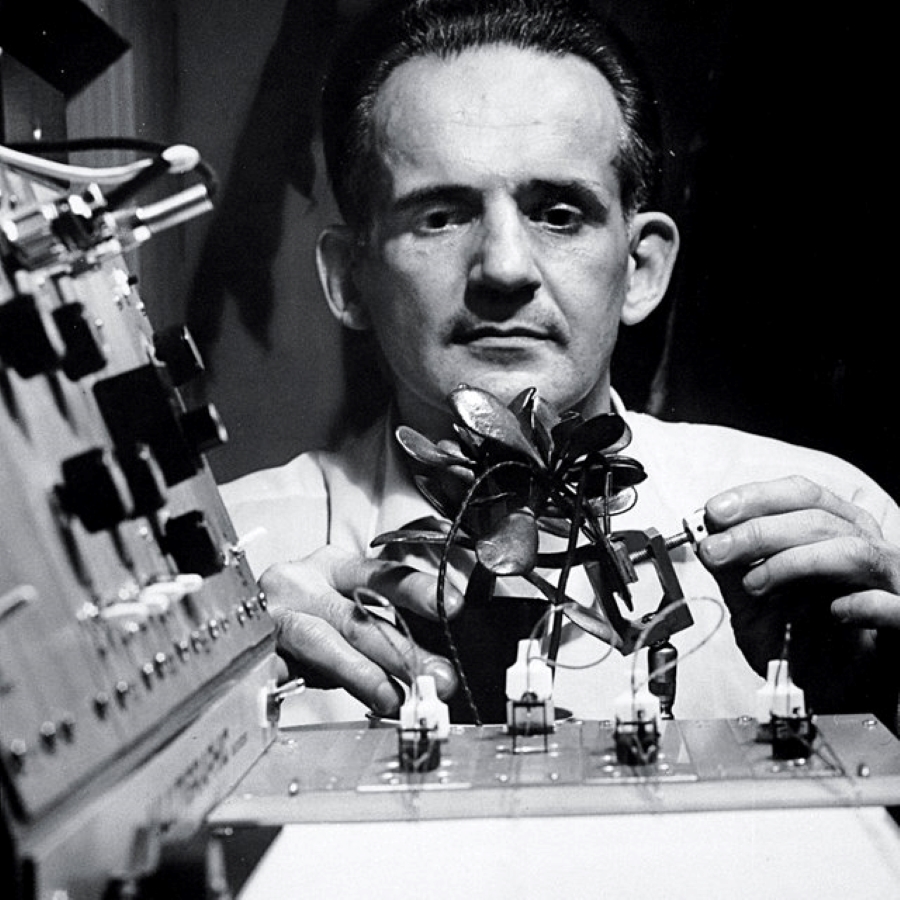

2. Plants Respond to Human Emotions (Cleve Backster's Polygraph Tests, 1966)

In 1966, Cleve Backster, a former CIA polygraph expert, conducted experiments that suggested plants could perceive and respond to human emotions. By attaching a polygraph machine to a plant's leaf, he observed electrical responses akin to those of humans experiencing emotional stimuli. Notably, when Backster merely thought about harming the plant, the polygraph registered a significant reaction, implying the plant sensed his intent.

While Backster's methods have faced skepticism and calls for more rigorous scientific validation, his findings opened the door to exploring plant perception in unprecedented ways. If plants can indeed detect and respond to human thoughts or emotions, it would suggest a level of awareness and interaction previously unacknowledged in botanical science. This line of inquiry challenges the anthropocentric view of consciousness and invites further research into the subtle ways plants may communicate or sense their environment.

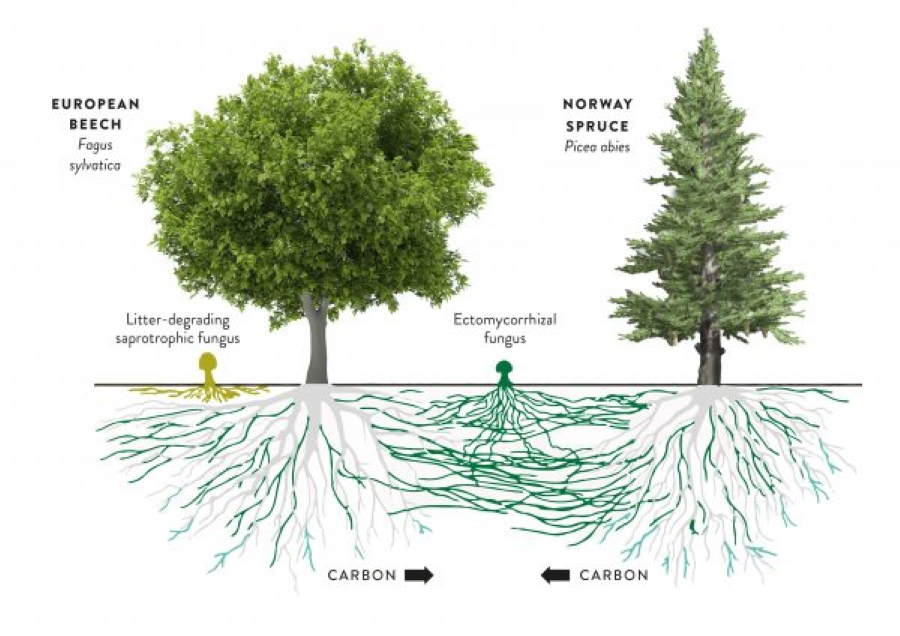

3. Trees and Plants Communicate Through an Underground Network ("Wood Wide Web")

Forest ecologist Suzanne Simard's research unveiled a complex underground network through which trees and plants communicate, often referred to as the "Wood Wide Web." This network, formed by mycorrhizal fungi connecting plant roots, facilitates the exchange of nutrients, chemical signals, and information about environmental threats. Older trees, termed "Mother Trees," have been observed to support younger saplings by transferring essential resources and signaling danger.

Simard's discoveries highlight the interdependence and cooperative behavior within forest ecosystems, challenging the notion of plants as solitary organisms. The ability of trees to "will" their nutrients to the next generation upon dying suggests a level of foresight and communal support. These insights not only deepen our understanding of plant ecology but also underscore the importance of preserving these intricate networks that sustain biodiversity and forest health.

4. Gaia Demonstrates Plant Consciouness

The video explores the intriguing concept of plant consciousness, suggesting that plants may possess a form of awareness akin to intelligence. It begins by referencing ancient beliefs about plants being conscious beings, a notion currently debated in scientific circles.

The video argues against the traditional view that consciousness is isolated to human and animal brains, proposing instead that it could extend across all biological life, including plants. Key points include how plants react to their environment, potentially make decisions, and may even show memory.

Examples of scientific experiments highlight plants’ responsiveness to stimuli, implicating a profound interconnectedness across life forms facilitated by shared resources like water. Ultimately, it challenges readers to reconsider their understanding of plants as sentient beings, emphasizing the need to recognize their contributions to human existence.